A friend recently said on her weekly writing podcast that she believes writers have a responsibility to learn everything they can about other cultures, not only to make sure they represent characters accurately, but to supplement any deficiencies in their own education and experience.

With that in mind, I suggest that as consumers of media (news, social, anything where you get your information from someone via video or audio), it is our responsibility to determine that what we see and hear on the news or the Internet is real.

Last week, I took a class on LinkedIn Learning called “Understanding the Impact of Deepfake Videos.” The course was released by LinkedIn August 13, 2020, and features Ashley Kennedy, managing staff instructor at LinkedIn Learning.

If you’re like me, you’re wondering what on earth a Deepfake is.

What is a Deepfake?

Deepfake is a mash-up of Deep Learning and Fake. Deep Learning is a method computers use to learn and study someone’s facial expressions so well that the computer can then predict how an image of that person would move while talking. Or the computer listens to so much audio of a celebrity or politician that it can listen to an actor saying something and can then convert what the actor says into the celebrity’s or politician’s voice.

In effect, with today’s video and audio technology, a talented computer operator could make it appear that someone said and did something that they never actually said or did.

How is that possible, you ask? Aren’t the manufactured videos obviously fakes?

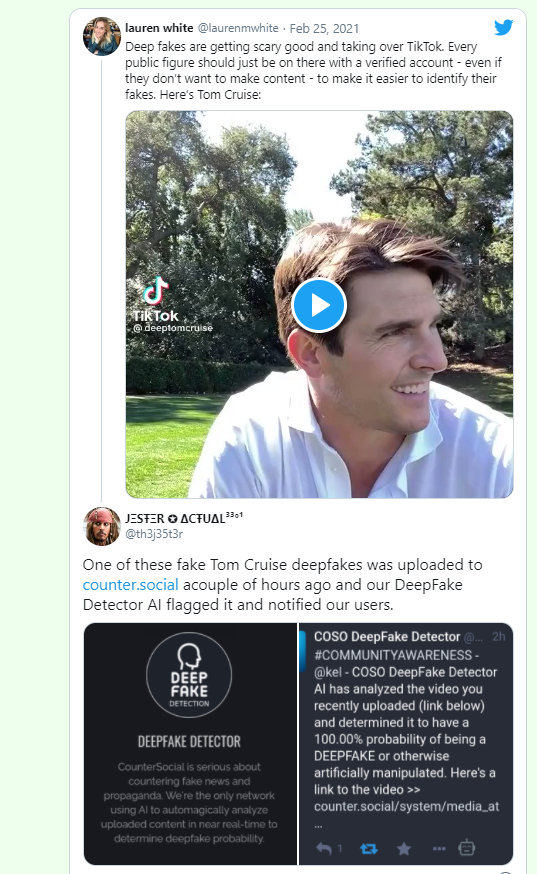

The two screenshots of Deepfake videos of Tom Cruise and Barack Obama that appear above are just two examples. Could you tell they weren’t real? Sometimes, you can’t believe your eyes or your ears. Especially when it comes to Deepfakes.

Moon Disaster Project

Within the LinkedIn Learning course, the video used to demonstrate Deepfake technology was produced by the MIT Center for Advanced Virtuality. This video focuses on the 1969 moon landing and a speech that was written for President Nixon, but never delivered.

The contingency speech was written in case the moon landing expedition went wrong and Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were stranded on the moon. Thankfully, the speech never saw the light of day, but the MIT group, along with a couple tech companies, produced a video in which President Richard Nixon actually delivers the contingency speech. It’s called In Event of Moon Disaster.

For MIT’s moon launch disaster video, they took actual footage from the 1969 moon landing and re-edited it, spliced it together, changed camera angles and speed, and used actual sounds from the original to make it appear more dangerous, according to LinkedIn’s Kennedy.

Positive Uses

Kennedy pointed out that there are many positive ways this technology can be used. Movie producers can change dialogue without calling the actor into the studio to re-record a soundtrack. And if an actor is not able to complete a project, the technology can be used to insert the actor’s likeness and actions in scenes the actor was not able to complete.

It can also be used to improve voice quality and even remove accents. And what about someone who has lost his or her voice? Rather than using augmentative communication devices with robotic voices, a more natural voice can be used.

Dangers Are Obvious

But the dangers are significant. Deepfake developers tend to target social media, because it is so easy for the videos to spread quickly, Kennedy said in the class. And even if a video is identified as being untrue or manipulated, the damage to the subject of the fake video is already done.

In the LinkedIn class, Noelle Silver, vice president of digital technology at NPR and a well-known public speaker on artificial intelligence and communications, was interviewed.

She said that Deepfakes breed deception and mistrust. But just as Deepfake technology is getting exponentially better, so is Deepfake detection technology.

Detecting Deepfakes

At the end of 2019, Facebook organized a Deepfake Detection Challenge. The competition drew more than 2,000 participants (individuals and companies) that tested their Deepfake detection models against a publicly submitted dataset of videos as well as a “Black Box Dataset” of videos provided by Facebook.

According to a report on the project, “The top performing model on the public dataset achieved 82.56 percent accuracy. But when evaluating the entrants against” the Facebook-provided dataset, that figure dropped significantly to 65.18 percent accuracy. That means the best AI and computer minds in the world still could not detect that almost 35 percent of the videos they evaluated were fakes.

What Can You Do?

How can you do your homework before you “Like,” “Share,” or “Comment” on a video that seems to be a little “off?”

Your first step should be the default for most of us – Google it. If someone of any importance or renown has said or done something even a little bit outrageous, it most certainly would be reported by many media outlets.

Then there are the traditional fact checking sites: FactCheck.org, Snopes, MediaBiasFactCheck.com, and Politifact.com, to name a few.

According to Silver, “Our brains default to truth. We tend to believe what we see.” Sometimes, we need to suspend that default belief and do some digging.

Here is a more in-depth look at MIT’s moon landing disaster video: Tackling the Misinformation Epidemic with “In Event of Moon Disaster.”

Tell me what you think of Deepfake technology in the Comment Section below or email me at susie@stix-n-stonez.com

Until next week,

Susie from Stix-N-Stonez

2 thoughts on “We All Have A Personal Responsibility”

Thanks for the information, Susie. I had no idea that something like this was going on! I appreciate your using this space to not only give us opinions but to also keep us informed. Thanks, sis!

Thanks, Chris!

Comments are closed.